Sponsored Listings:

After years of long-term travel, I have yet to find a way to fully avoid feeling the effects of jet lag. Colleagues have said that they barely notice changes to their circadian rhythm, and long-term travel leads to more of the same. But my own body is different. As an insomniac who turned to meditation to minimize my panic before sleep, jet lag has been a real thorn. At the beginning of my travels, I handled the woozy dissonance with mid-afternoon naps and a week of wandering through life as a zombie. It wasn’t enough.

That feeling on the descent into a new city after a long haul flight, both excited and exhausted, waiting for jet lag to set in

Origins of Jet Lag in Popular Culture

Jet lag is a fairly recent term, which makes perfect sense because airplanes are a fairly modern invention. The question I had in writing this piece was: when did it first pop up in writing?

There is a May 1958 piece in Popular Science magazine that alludes to its effect on our bodies. Called “Trials of the Jet-Age Traveler,” it warns that flying around the world:

“at nearly the speed of sound will throw your eating and sleeping schedules off as never before. … You can make a mental adjustment by simply resetting your watch while whizzing over the time zones of Paris, Beirut or Karachi. But your body doesn’t change its routine so easily.”

Then there was a 1969 study by the Federal Aviation Administration, entitled “Time Zone Effects on the Long Distance Air Traveler,” which notes that pilots in the 1930s submitted early write ups about body clocks. The study is clear to mention that as of 1969 there was no definitive study about jet lag, but that desynchronization of the circadian system was a serious problem for travelers and pilots alike. (I also like that its final suggestion is moderate exercise and a warm bath to help induce sleep.)

From government studies, jet lag hopped into popular culture via the media society consumes. Per an Air and Space Magazine article, the first appearance in newspapers was from a Los Angeles Times article on February 13, 1966, by Horace Sutton:

“If you’re going to be a member of the Jet Set and fly off to Katmandu for coffee with King Mahendra, you can count on contracting Jet Lag, a debility not unakin to a hangover. Jet Lag derives from the simple fact that jets travel so fast they leave your body rhythms behind.”

Google’s nGram graph for jet lag in books from 1800-2008 show that it was first mentioned in the late 1940s, with the term gaining traction throughout the latter part of the 20th century, peaking in the year 2000.

What is Jet Lag?

Jet lag is a chronobiological problem, as is shifting your body clock when undertaking shift work. When we travel long distances, our circadian rhythm (internal body clock) is temporarily out of synch with the new destination’s time. This means that internally we anticipate dawn and dusk to fall at certain times, which are suddenly at different times than what’s happening outside. The desynchronization affects not just sleep, but also body temperature, blood pressure, hormone regulation, when we get hungry and how hungry we are. Jet lag is the lag time between our internal body clock and the place we are now inhabiting.

You know that feeling when you wake up at 3am after a long-haul flight and you wince rolling over to check the clock because you just know it’s not actually day time but your body is all NO GET UP NOW IT’S NOT NIGHT IT’S ALL A LIE? Yeah, that. When this happens, I feel like a perpetual daytime / nighttime bird, unaware of which is which, dreading the middle of the night awakening.

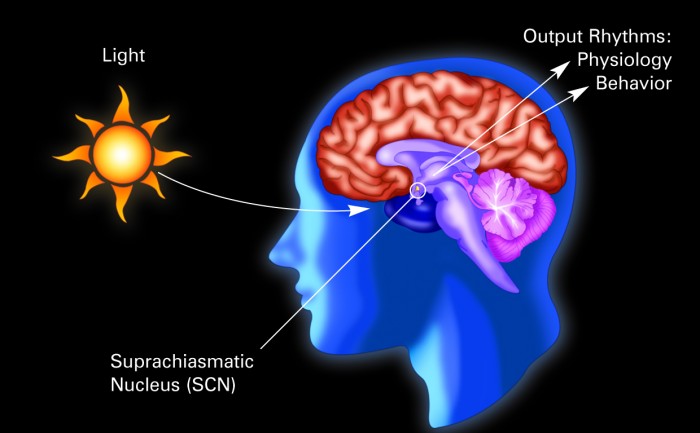

Our body clocks run on a slightly longer than 24-hour cycle, with a “master clock” in our brain that uses our exposure to light to coordinate all of the workings of our organs. Consisting of a group of nerve cells in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (or SCN), this master clock is located in the hypothalamus, “an area of the brain just above where the optic nerves from the eyes cross.” Genes also influence the body’s clock and circadian rhythms, which helps explain the variance in adjusting to time change from one person to another.

The body’s production of melatonin, a sleep hormone produced by the pineal glad to signify to our body that soon it will be time for rest, affects our body’s internal time measurement system. That system is also influenced by the direction we travel; heading west is easier on our body than flying east.Per Dr. Smith L. Johnston, a flight surgeon and the chief of the fatigue management team at NASA, it takes about a day to adjust to each time zone we cross. But a new study shows that not only is it easier to recover from westward travel, but that hopping over a few time zones might be harder on our body clocks than a larger gap.

Per a July 2016 New York Times piece summarizing that study:

For example, it would take you about eight days to recover from a westward trip across nine time zones, if you did nothing to fight it. But if you cross the same number of time zones going east, recovery would take more than 13 days, according to the model. This recovery time is worse than if you flew smack across the globe, crossing 12 time zones, which is about the distance from New York to Japan.

This is all because the body’s internal clock has a natural period of slightly longer than 24 hours, meaning that the body has an easier time with lengthening the day (heading west) than shortening the day (heading east).

I find it takes me a week to adjust when returning from Vietnam, but with the tips below I’ve minimized the interference with my day-to-day living. Prior, I simply curled up in a ball on the carpet at 3pm and called it a day.

My Tips for Combating Jet Lag when I Travel

This list of tips has not been reviewed by a doctor, but are simply what I have found works for me as I’ve traveled the world. I’ve found a combination of various tips, culled together from my reading and testing, that truly mitigates the effects of jet lag. As a long-term traveler jet lag is a significant problem. I was incentivized to make it more bearable.

1. Small Doses of Melatonin

When night falls and there is less light input to the SCN, melatonin secretion increases. At dawn, the levels of melatonin produced by our bodies drop again and the body’s daytime circuits take over.

When night falls and there is less light input to the SCN, melatonin secretion increases. At dawn, the levels of melatonin produced by our bodies drop again and the body’s daytime circuits take over.

I use melatonin in two different ways, both in way smaller doses than the dosing recommendations on the over-the-counter medicine you buy at your local pharmacy or on Amazon. Less is more for me, else it spills over into the next day.

The dosage recommended on these bottles is quite a lot higher than studies have shown our bodies need, and while I am not a doctor I have found great success with a severely scaled-back dosage. Even less dosing (0.3mg as the ideal) is effective when testing for insomnia in 50-years old or more patients.

When I take the recommended doses, even with as small as this 3mg pill, I find that the next day I am extremely irritable, overly hungry, and generally not someone you’d want to hang out and share a meal with.

For my jet lag, I take 1/4 of a 3mg tablet just before bed. Often I will wake up in the middle of the night WIDE AWAKE because my master clock thinks it’s daytime — see above for daytime/nighttime bird video. In those cases, I will take another 1/4 of a 3mg tablet and then always sleep through the night.

Another option is Sprayable Sleep, sold via their own website and had a successful Kickstarter as they geared up for launch. Sprayable goes onto your skin, not under your tongue, and each spray is directly absorbed. For super sensitive people, this might be a better option as you can control the dosage even further. If interested, a study about use of transdermal melatonin, here.

2. Restricting Blue Light Exposure at Night

Part of regulating circadian rhythms is to get in the habit of signalling to your SCN and your body when it’s time for bed and when it’s time to wake. In a modern world, we are exposed to quite a lot of artificial “blue” light (even though it looks white), a daylight signaler to our minds. Be it LEDs, fluorescent lighting, or the backlit screens of our portable devices, it’s easier for our bodies to get confused. It’s even more confusing when your body clock thinks it’s halfway around the world.

The title of a January 2015 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences summarizes it all: “Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness.” Per that study, people not only produce 55% less melatonin when using an iPad at night, but after tucking into bed thereafter it took extra time to fall asleep. Further, the sleep had less rapid eye movement (REM) time. The next morning, those iPad users felt sleepier and had difficulty feeling awake.

In contrast, those who read books instead awoke with more alertness. If that wasn’t bad enough, the study found that next night the same iPad users had their circadian rhythms out of whack, delayed by well over an hour. This means that they began to feel tired later, because they had read on a blue-light device before bed the prior evening.

Since I have started restricting blue light at night, I have found it a lot easier to shift my body’s clock when needed, have slept more soundly, and have felt more alert in the morning.

Here are some ways to do so:

Using F.lux on Your Laptop

I have personally forced every friend and family member who doesn’t have F.lux on their laptop to download it immediately, and promised them that it would change their lives. I’ve never found one program that has this big an impact on my sleep cycle and comfort as I work in the evenings.

I’ve always been more productive in the evenings, usually starting around 4pm. I will happily work away well into the night. And of course, after pecking away for hours, I found it difficult to shift into sleep. F.lux automatically blocks blue light from your screen at sunset based on your location, and lightens it in the morning. It’s a free programme, and I encourage you to donate to them because it’s basically pillows for your eyes.

I’m not affiliated with them, nor did they ask me to write this. I just evangelize wildly because it’s made such a huge difference to the way that I can work productively in the evening without feeling terrible the next day.

Example of screen differences from day to night with f.lux

Using iOS’ New ‘Night Shift’

If you’re using an iPhone or iPad, the new “night shift” mode allows you to block blue light, essentially “Fluxifying” your device for evening use, which can help you sleep.

Using Blue-blocking Glasses

Using Blue-blocking Glasses

If you’re not looking to add a programme to your laptop, you can block your blue light using these extremely sexy (ok not so much) orange glasses: Uvex Skyper Blue Light Blocking Computer Glasses with SCT-Orange Lens. These allow you to read on whatever device your heart desires, but block blue light in the process.

3. Minimize Jet Lag by Shifting your Time Zone Early

Many pieces about jet lag address what happens when you land, but I have found that preemptively signaling to my body that I am “in” that new time zone helps shorten my adjustment period considerably.

How do I shift my time zones ahead of my travels?

- I set F.lux to the new time zone 5 days before leaving, so my laptop blocks blue light during that country’s nighttime hours.

- At the same time as I start my F.lux schedule, I take melatonin at what will be the beginning of dusk in my new destination. So if I’m heading to Saigon but presently in Montreal, I’ll take 1/4 of a 3mg pill of melatonin at 9am Montreal time for the 5 days leading up to departure. This does mean that I struggle more with sleep during those few days, but the process truly limits time’s impact upon landing.

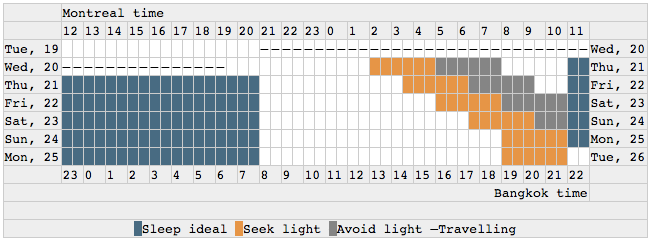

Sample Jet Lag Rooster timetable

4. Morning Exercise

A short but effective tip: work out in the mornings when you are in the new time zone, getting your blood flowing and waking you up even more. Initially, I was more awake at night and exercised then. Doing so simply woke me up further and made it harder to sleep.

5. Meal Time Limits

As with limiting blue light and adjusting sleep schedule, meal times are an important factor in mitigating jet lag’s effects. Since the SCN affects not only sleep but also our hunger levels and many other systems within our body, eating at the wrong times can signal to your body that you’re not where you actually are.

Airplane rides do try to serve the “correct” meals for the coming time zone shift, offering breakfast before a dawn landing for example. But after arrival, I tend to crave my meals during my departure time zone’s dining hours. While it doesn’t make it easy during those first few days, I try to rigidly stick to the new time zone’s meal hours. I often have low blood sugar and can get shaky between meals. A glucose tablet does the trick to help keep my body on schedule. Grape is my fave.

Further Reading About Jet Lag and Sleep

The Rhythms Of Life: The Biological Clocks That Control the Daily Lives of Every Living Thing: By circadian neuroscientist Russell G. Foster, Rhythms of Life is a wonderful and accessible introduction to the world of daily and seasonal biological rhythms.

Internal Time: Chronotypes, Social Jet Lag, and Why You’re So Tired: By chronobiologist Till Roenneberg, Internal Time investigates the connection and conflict between biological and social clocks and how social jet lag affects almost everyone.

Dreamland: Adventures in the Strange Science of Sleep: David K. Randall on the science behind sleep, a book he was inspired to write when he started sleepwalking. In Dreamland, Randall explores the research about sleep and how it changes by gender, age, and all of the other factors that impact an activity that takes up 1/3 of our lives.

Sleep: A Very Short Introduction: Russell G. Foster and Steven W. Lockley on why we sleep and how much is enough for a modern human. From sleep disorders to quality of life, the authors examine the relationship between sleep, work, and the impact of an always “on” society.

Jet Lag is a Reality I’ll Take

Ultimately, jet lag isn’t that bad. It’s a temporary state, and we know it. It’s a mindless torture of teeny chunks of time, one that allows us to let go of life’s reigns a little bit, and sink into disorder.

The tips I’ve written about here have helped minimize jet lag’s effects on my life, but when I am in the throes of it I try to enjoy it also. As Pico Iyer said in his New York Times piece on the subject:

Fourteen hours later, I’m on a different continent and hardly able to imagine the life, the home, I left this morning. It’s as if I have switched into another language — a parallel plane — and none of the feelings that were so real to me this morning can carry through to it. It’s not that I don’t want to hear them; it’s that they seem to belong now to a person I no longer am.

There is something gloriously discombobulating about emerging from a long flight into the fog of a new place. So even if the impacts of jet lag lessen but never go away fully, there are far worse states of mind to inhabit.

-Jodi

Sign up to receive the best of the web, straight to your inbox.

Links I Loved, my monthly roundup of interesting reads.

(No spam, just fascinating links to learn from.)

The post Why We Get Jet Lag and 5 Tips for Making It Less Painful appeared first on Legal Nomads.

Source: legalnomads.com