Sponsored Listings:

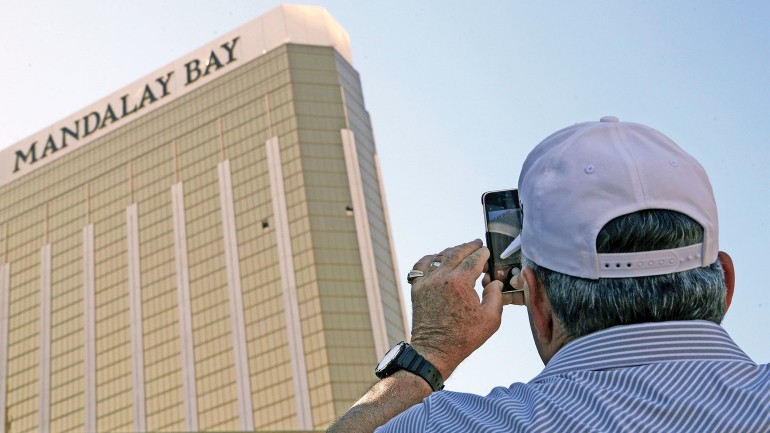

Even before Oct. 1, when a gunman in a hotel room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay sent a hail of bullets down on the Route 91 Harvest Festival, killing 58 and wounding 489, Las Vegas had lived with the uneasy knowledge that something like this could happen.

“Las Vegas is a target city,” Wynn Resorts CEO Steve Wynn told reporter Jon Ralston in a September 2016 interview with KTNV. Not only is the city’s perceived amorality offensive to some, he said, but “we have all these arenas and showrooms, these massive amounts of people on the Strip.”

To care for and protect the roughly 43 million people who visit Las Vegas annually, as well as the cash in the casinos, Vegas resorts have famously robust security — large teams of private staff, surveillance cameras that monitor virtually every inch of public space and strong relationships with law enforcement agencies that often have officers on site, working nightclubs or special events.

“We have more equipment and technology, we have more security per capita than any other resort-type city in the U.S.,” asserted David Shepherd, CEO of the security consultancy Readiness Resource Group. A 24-year veteran of the FBI, Shepherd for seven years was the executive director of security for the Venetian.

In Las Vegas, Shepherd said, security chiefs meet monthly with the police, the FBI, the Secret Service and the Drug Enforcement Agency to discuss best practices. Intelligence about potential threats is distributed to resorts by the Southern Nevada Counter Terrorism Center, a “fusion center” staffed by employees of 27 agencies.

Given the vast number of visitors flowing through the city — more than 800,000 per week — and the hard partying that often accompanies trips to Sin City, the Strip is actually remarkably safe, said Mehmet Erdem, associate professor at the William F. Harrah College of Hospitality at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV).

“If you look at the number of robberies or stabbings or muggings, we should have something every day, and we don’t,” he said. “I think that’s a testament that the system is working.”

Still, the system didn’t prevent shooter Stephen Paddock from assembling a horrifying arsenal in his wrap-around suite overlooking the Strip or wreaking havoc on 22,000 country music fans gathered to hear headliner Jason Aldean’s closing set.

Given all that preparation and intelligence, the question on everyone’s mind in the wake of last Sunday’s tragedy is whether or not it could have been prevented.

“There’s no easy answer to that,” said William H. Sousa, director of UNLV’s Center for Crime and Justice Policy. “We’re dealing with a situation that really hasn’t occurred at this level before.”

Most active-shooting training focuses on ground-level threats seven to 10 feet from victims, Shepherd said, not elevated aggressors targeting people below. The most famous comparable case dates back 51 years to when a gunman killed 17 people from atop a tower at the University of Texas in Austin.

As more information comes out, the security community will study what happened in Las Vegas and address vulnerabilities through training, awareness and perhaps increased security measures, just as it does in response to incidents all over the country and the world.

“There’s a lot of things that are going to come out of this,” Shepherd said. “There’s a lot of things that may change. The No. 1 mission on our minds is the safety of our guests under every threat condition.”

Clark County is in the process of installing bollards along sections of Las Vegas Boulevard. Those are the metal barriers intended to separate street traffic from the sidewalk and protect pedestrians from vehicle attacks such as those in Europe or incidents like the one in 2015 when a woman drove onto the sidewalk in front of Planet Hollywood, killing one and wounding many others.

One response to the Route 91 concert shooting may be better training for non-security staff at Strip casinos so that housekeepers, VIP hosts and front desk workers, the employees who are most likely to come into contact with guests planning something nefarious, are better equipped to assess suspicious behavior and report it when necessary.

Those kind of security adjustments likely won’t impact guest experience and would go unnoticed by most of the people playing craps or grabbing cocktails. But some of the measures being discussed in the wake of this month’s shooting are far more invasive and could prove to be impractical in the long term.

In the days immediately following the Route 91 concert attack, Wynn and Encore stationed security staff at entrances to both properties, searching bags and scanning visitors with hand-held metal detector wands. By midweek, those precautions had reportedly been relaxed. A spokesperson for the resorts declined to comment on the changes.

“It’s just to show we mean business,” Erdem said of the enhanced screenings. “People constantly go in and out of these hotels. They’re like little mini-cities with multiple entry points. I honestly don’t think it’s pragmatic to screen everything and have metal detectors.”

The real challenge, experts agree, is balancing luggage checks and metal detectors with Las Vegas’ cultivated status as a destination for no-holds-barred escapism. In the immediate aftermath of tragedy, customers might be relieved to see tighter security. But a month from now, will visitors want to face additional scrutiny or wait in TSA-style lines to enter a casino?

“You want people to feel welcomed,” said UNLV’s Sousa. “You want people to have freedom of movement. You want people to have a fun, free experience. Balancing that with security concerns is always a major challenge. Overall, Las Vegas is a safe place to be.”

Sоurсе: travelweekly.com