Sponsored Listings:

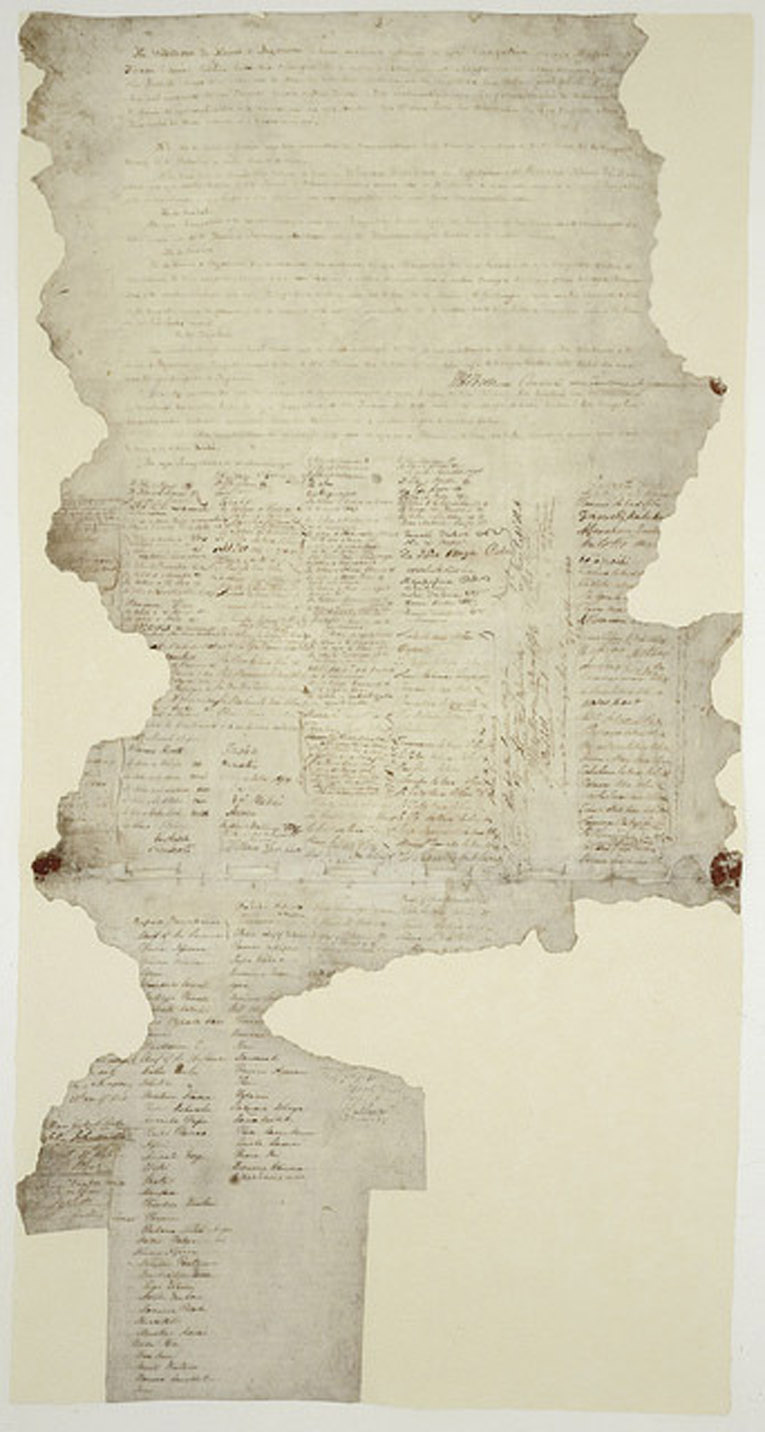

Their signatures are inky spiders. Spindly legs and fat, loopy bodies. They are Mrs Brown and Mrs Smith and Mrs Thomas.

They have relinquished their first names to marriage, but there is strength in their numbers. Legend says it was the great suffragette Kate Sheppard herself who mixed the flour and water paste that joined these voices together.

In 1893, hundreds of sheets of paper, containing almost 24,000 signatures, were rolled around a broom handle and unfurled in Parliament, in the first country in the world where women won the right to vote.

What were they thinking when they pressed pen to paper?

Sometimes, in her white lab coat and nitrile gloves, Vicki-Anne Heikell wonders. It is 123 years since the Suffrage Petition was presented, 177 years since the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, and 181 years since He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene (the Declaration of Independence).

Today, at Wellington’s National Library, the $7.2m exhibition of those documents opens to the public. He Tohu (“The Signs”) aims to preserve the country’s three most iconic and important constitutional documents for the next 500 years.

Heikell descends from Te Whanau-a-Apanui. She is one of three National Library field conservators who spent months examining these papers, writing condition reports (sample sentence: “UR corner Dog-eared, multiple folds and creases — now flat”) and making recommendations for their long-term survival. It was, she says, a highlight of a career that, for her, began with a 1980s holiday job on an East Coast meeting house restoration project, and the subsequent opportunity to train as a conservator in Canberra, Australia.

“As a Maori conservator, I want to be able to preserve the documents that reflect our past, or have our tupuna represented in them. I’m doing that for the mokopuna, or the future generations. I see my conservation work as speaking to the past, for the future.”

Heikell worked on the Treaty sheet sent to the Bay of Plenty and signed by her forebears.

“They’re more than their physical state. I guess they speak to nationhood, but they connect all of us to each other.

“These documents don’t sit in a vacuum of the past, they’re still relevant and present challenges and opportunities for debate.”

Heikell knows the material she worked on was carried by James Fedarb, a 23-year-old trader, who sailed to the Bay of Plenty, collecting signatures in Opotoki, Torere, Te Kaha and Whakatane.

“Conservators are very much about saying ‘perhaps’ and ‘likely’ and ‘possible’. But there are crease-lines and certain, more permanent, folds . . . you could surmise that he may have folded it up in a certain way to get it safely across in his satchel, that’s what I imagine, when he docked, and he would go and have a conversation with Whakatohea Te Whanau-a-Apanui. You could never say, definitely, but the folds give little clues and an insight into the history of those documents.”

And she wonders: “Looking all those signatures, you do reflect — what were they thinking at the time they signed? The very moment that they signed? When the nib pen was loaded up and they put the iron gall ink on . . . at that exact moment their tohu went on to the paper or the parchment . . .?”

The documents have been displayed in National Archives’ Constitution Room since 1990, but the room’s air conditioning was ageing, and the upgrade of National Library, presented an opportunity for a new, permanent exhibition and interpretative space (a request to send the Treaty and Declaration north, to the new Waitangi Museum, was declined — too fragile, argued Archives).

Light, temperature and vibration can harm these documents. On the parchment portions of the Treaty the ink is so unstable there is a fear signatures could literally fall off. It has survived fire (eleven loose-leaf sheets were rescued, in an iron box, from a burning official’s cottage in 1841) and it disappeared for years before being rediscovered in 1908, in Wellington’s Government Building’s basement — water-stained and chewed by rats. Heikell says conservators have been able to reconstruct exactly how it was rolled for storage, by aligning the rodent damage on different sheets.

DNA testing has revealed, for the first time, that the upper layer of parchment sheet signed at Waitangi was made from sheep’s skin and the so-called “Herald” sheet, that went to the South Island, was calf. But the work is not as “CSI” as people think, says Heikell.

“Less is best. We don’t want to put anything of ourselves on those documents. Archival documents are about telling a story. Just as interesting are the marks and scrapes and stains, caused during manufacture or possibly at the signing of the document itself. Those are all insights into its history.”

The three documents will be housed in atmospherically-controlled and alarmed display cases constructed by German firm Glasbau Hahn. The Suffrage Petition, at more than 200m long, has been a display challenge. (And fashion is a fickle mistress — all those inky names are fading, but the ones in fluoro green and purple pen, so contemporary and compelling in 1893, have fared the worst). It has been remounted on a roll, and different portions will be on display at different times. One page of the Declaration of Independence, the oldest of the documents, will finally be able to be viewed as a double-sided document, in a vertical mount that will allow visitors to get within 3cm of the text.

“They’re the iconic documents of the nation,” says Denise Williams, Archives New Zealand director of holdings and discovery, responsible for their physical shift to National Library. Staff practised the shift for weeks with specially weighted boxes. Travel contingency plans included a “safe place” for vehicles to get to, should an earthquake occur. The move was done before dawn, in keeping with Maori tikanga.

“They’re living documents in the eyes of the descendants of the people who signed them,” says Kura Moeauhu, Parliament’s senior Maori advisor and one of the tikanga leaders for the He Tohu project.

“In the Maori world, we believe that our ancestors move around at night. We wanted to make sure they were able to guide us through the move.”

Sоurсе: nzherald.co.nz