Sponsored Listings:

I’ve been waiting only a few minutes in the cobbled alley, when I see a small hatchback, perched outside the entry to San Telmo market, being honked at by a bulky rubbish truck.

Calle Estados Unidos is lined with century-old apartments and ancient shops. It could be in Paris, rather than Buenos Aires, apart from the large rubbish skips lining the street.

Mario Braun emailed me the day I arrived, so I correctly anticipated he would arrive “en punto”, on the dot. He spots me and swoops in. I jump into the passenger’s side, on the right, with the rubbish truck in pursuit.

An older gentleman, sporting a red-tinged grey goatee, suede jacket and cravat, Mario drives the Fiat Idea hard. He stops and starts, honks and curses at fellow motorists in the enormously wide, congested, central city avenues.

Before retirement, Mario was a flight attendant, with a side-line in tourist guiding, so he starts our tour in the car.

As we drive at a crawl past Buenos Aires’ Faculty of Engineering, Mario says the immense Parthenon-inspired edifice was built for famed first lady Eva Peron in the 1950s, as a base for her work with poor families. Eva never saw it completed, as she died of cancer aged 33. Her early death only fuelled “the myth of Evita”, Mario tells me.

When World Journeys director Chris Lyons arranged for Mario to give me a personal guided tour of Recoleta Cemetery, he informed me Mario’s claim to fame was that he brought Evita’s body back from Madrid in 1974.

I ask Mario about this in the car. He explains he and the other crew were all known anti-Peronists. Only the pilot and first officer were Peronists. The mix was chosen to get Eva’s body home without any more funny business.

This led on to the bizarre story of Eva’s body’s odyssey. After her death in 1952, Eva’s body was embalmed and kept in the unionists’ hall, near Casa Rosada, a pink-stoned Parliamentary building Mario could wave towards at that moment, to inspire union action.

Juan Peron didn’t retain power for long after Eva’s death and, when a military junta took over, they spirited Eva’s troublesome body away to a grave in Milan, which was marked with a false name. Many years later, times changed and the military moved Eva’s body to Madrid, where Juan Peron was living.

Juan was re-elected in 1973, but died a year later. His third wife, Isabel, took his place, but struggled in the role of president. In a bid to gain popularity, Isabel ordered Eva’s body returned to Argentina. Despite his political views, Mario says, when he saw Eva’s well-preserved body, he was touched to be a part of history.

Soon after, there was yet another kidnapping of the body. Eva’s family said that was enough and they were allowed to bury Eva in the Duarte family tomb at Recoleta Cemetery, on the condition her body no longer be used for political purposes. So Eva is now firmly encased in concrete and buried deep underground at Recoleta Cemetery.

As we pass Luna Park, a lumpy pinkish event centre, Mario says this is where Juan Peron met his future wife, then Maria Eva Duarte, at a fundraising fiesta for earthquake victims. Eva was an ambitious actress who made sure she sat next to the up-and coming colonel. She soon moved into his apartment, evicting his girlfriend. A year later, in 1946, they were married and he was president. Well, that’s how Mario explains it.

When I ask about her reputation for furthering the rights of women and the poor, Mario concedes Eva was a powerful woman at a time when that was unusual.

So, at Recoleta Cemetery, while most people head more or less directly for Eva’s tomb, we focus on symbols. Mario has a degree in art history and has written a book about the symbols of Recoleta Cemetery. This was largely because he was tired of showing people only Eva’s tomb, when the cemetery is so much more than that.

It is an open-air museum, with every imaginable architectural style and symbols from Roman and Greek times, through the Etruscans and the Middle Ages.

Common symbols include an egg-timer with wings, reminding us how tempus fugit, an owl representing wisdom, palm leaves and an innocent lamb.

Recoleta became a public cemetery in 1822, when the authorities decided to no longer allow church burials. Now around 5000 people are buried there, including pretty much all military and political leaders, along with the city’s wealthiest families.

So, a tour of the cemetery offers a lesson in the history of Argentina, especially Buenos Aires’ heyday in the 1800s when it was one of the world’s leading exporters and a wealthy economy.

Mario points out Freemason symbols, such as a mathematical compass, and an eye inside a triangle. One Freemason is buried in a pyramid with a triangular base. Many of Argentina’s leaders were Freemasons, but on the quiet, as the free thinkers were often distrusted by governments.

The cemetery is a remarkably peaceful place to wander around, especially with an erudite guide. Mario points out bas-reliefs depicting the stages of life, childhood, romance and ageing, and says the tombs celebrate life, rather than mourning death. He gets me to peer inside a sarcophagus, to see how they go down several stories to house many generations of families.

We admire a beautiful art nouveau mausoleum, featuring a statue of a young woman, Rufina Cambaceres. The legend goes that, in 1902, the 19-year-old fell into a coma and appeared dead, so was buried. A few days later, cemetery workers heard noises from the tomb. They opened the coffin and found her dead, but with torn nails and scratches on her face from trying to escape. The family denies the story, but it makes a great graveyard yarn.

We stop momentarily at Eva Peron’s tomb, one of the only ones to be adorned with artificial flowers. I just have time to get a blurry photo, while Mario tells me we are actually standing above her body, before he whisks me away to make room for a noisy school group.

We move on to other legendary tombs, such as a statue of a young woman, who died in an avalanche in 1970, while on holiday in Austria. Her dog’s bronze nose is rubbed to shiny, as it is said to bring good luck.

Mario and I repair to a nearby European-style café, La Biela, and sit at an outside table next to a wide avenue and leafy plaza. Service from waiters in black wearing starched aprons is impeccable, if a little intimidating.

Over coffee, Mario shares more of his story. During the time of the military junta, you only had to be in the contacts book of someone they were interested in to be taken into custody. He disappeared for a week in 1976, and was taken to several secret detention centres, where he was tortured for information. Luckily, he had friends in diplomatic circles who secured his release.

Mario was put straight onto a plane to Germany, where he spent a year negotiating to get his daughters and wife freed to join him. The authorities held his family’s passports, so he wouldn’t go public with his story. Eventually, he agreed to give up his government job with the airline and any right to compensation, in return for his wife and daughters’ release.

Mario spent the years, until Argentina lost the Falkland War and the military started losing support, in Germany, Italy and Spain. When democracy returned, in 1983, he came back and was compensated. He got his government job back, as head of cabin crew, at the same level and with a pension valued as if he had unbroken service. That was under a democracy.

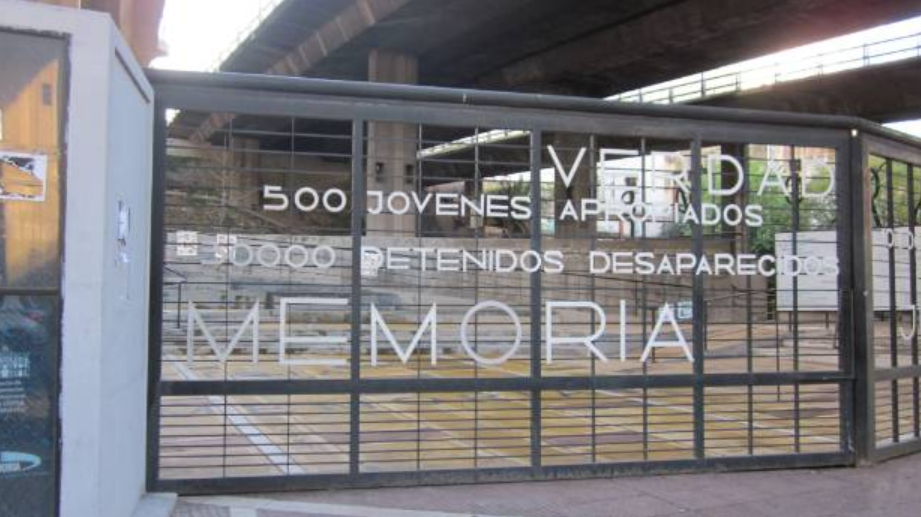

Mario puts the figure of disappeared at 6000 to 10,000 – lower than the official figure of 30,000, but still too many.

I ask how the experience has affected him and Mario says realising how fragile life is puts things in their real value.

“I am not running behind money. I am running behind friendship, knowledge.

“I am not running behind political relevance. I prefer my books.”

When we get the bill, I offer to pay, but Mario says, “No intiendo Ingles.” Suddenly, he doesn’t understand English.

On the drive into the city, I ask Mario why he is anti-Peronist. They were populists, he says, and fostered a personality cult. They appealed to the lower classes, but didn’t foster development. Plus, they had fascist sympathies and welcomed Nazis to Argentina after the war. Nazi fugitives didn’t need any special visa and mostly lived in freedom under their own names. Also, when the military took power, Juan Peron fled to then fascist countries, Paraguay, Panama, Venezuela and Spain.

I reflect on how Buenos Aires seems battered by decades of struggle and how everyone I meet puts that down, in a large part, to corruption and the ever-striking unions. Mario says no government, other than the military, has seen out its term, but rather has been deposed by militant union-driven protest action.

I find it hard to categorise everything he has told me in terms of left and right as I understand them from living in New Zealand.

I can see why the free-thinking Freemasons fascinate Mario – even though he hasn’t joined them. Mario is not a joiner.

Getting there

Air New Zealand flies direct to Buenos Aires, three times a week and five times a week from early December to early March, while LATAM flies daily from Auckland to Santiago in Chile, where you can get a connecting flight to Buenos Aires.

A taxi fare from one suburb to the next will generally cost under $10.

Staying there

I budgeted around NZ$80 per night for accommodation and stayed in a range of options, from Airbnb to hostel to luxury hotel, all appealing in their own way.

Good to know

The Argentinian Government organises daily English-language tours in different parts of Buenos Aires, including Recoleta Cemetery, for free and all at 11am.

A delicious meal and a glass or two of wine in a bar or restaurant will set you back about NZ$20.

The seasons correspond to ours, with summer reaching 40 degrees Celsius and winter very cold. Spring and autumn are good times to visit and, in October, I enjoyed mainly fine weather in the 20Cs.

Source: stuff.co.nz