Sponsored Listings:

Phil Vine takes a river cruise with ‘all the patience in the world’.

If ageing is an art form – and it probably is – the Murray Princess is a floating gallery, a boatload of portraits of our future selves. The perfect place to contemplate who you are, and the masterpiece you may become.

Not to mention the actual oil paintings outside. Majestic ochre cliffs and crackling eucalypts. Timeless landscapes straight from the brushes of Heysen and McCubbin. They drift past at a leisurely 12km/h while an attendant and whimsical crew see to your every need.

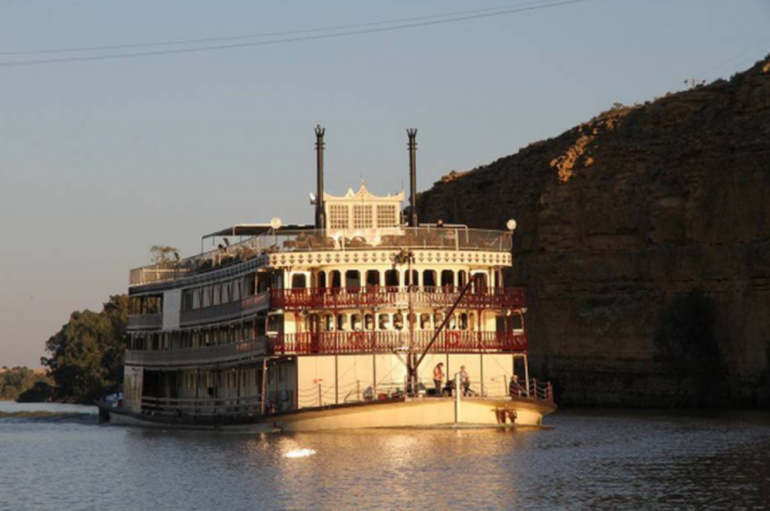

The Princess is a paddle steamer, powered by diesel. Droplets of water from the huge wheel glint in the light. Little fish are deposited by the blades on to the back of the boat.

The pelicans follow our slow progress, looking on hungrily – or maybe they’ve just been unfairly typecast by those cavernous beaks. Pelecanus conspicillatus.

From the top sun deck it feels as though we’re barely moving. The effect is mesmerising. You find yourself hypnotised by the warmth on your back and the gentle chugging of the engine. The river is so still it throws up postcard reflections of pale green gums and light orange escarpments the hue of the presidential ‘do. You lose yourself in a book for an hour, or two, or three, interrupted only by occasional blasts on the horn to warn the ferries, or a welcome call to dinner or lunch or breakfast.

At our table of whippersnappers, know-nothing journalists in decades three to five, we play a slightly disrespectful game. Pick the passenger you’d most like to grow into. For the most part the other passengers range in age from their 70s to late-90s. Proud to say that my mum, whom I’d brought along as a travel buddy, was a popular choice. Di’s a sprightly 82. Even more nimble than the persistent woman who kept trying to sit on the captain’s knee at dinner.

My own choice of future self was David, a Mancunian in his 80s. He’d moved to Perth with his family aged 38 to work as an engineer. Rangey, engaging, with bright sweaters and an excellent set of ears, Dave had stories to tell. He was a frequent floater on the Princess and something of an expert on river lore.

“Did you know?” He interrupts me politely as I sit writing in the ship’s library. The old paddle steamers used to stop along the way and pick up stacks of firewood from the riverbanks, leaving money for the woodcutters. Just like petrol stations. “Interesting,” I mumble.

“One captain never paid his bills so the woodsmen thought they’d sort him,” says Dave.

“They stuck a stick of dynamite in a hollowed-out log. A few days later the boat’s firebox exploded sending the ship’s cook flying a hundred feet in the air.” Now I was interested.

Once I got to know him, it seemed like just the sort of wheeze that Dave would pull. He spent all of our lunch at Banrock Station Winery trying to convince me to swipe a branded glass for him. “It’s Okay, Phil – I’m a collector not a hoarder.”

And Banrock Station by the way – what a surprise. In New Zealand it may be the last word in cheap red, but it’s worth seeking out their more expensive vintages. Some amazing drops. Even more amazing, their sustainable wetland programme, which is worth supporting the label for.

Freebies are a sure bet to keep the post-war generation happy (and skint journos for that matter). The lunch at Banrock is great and gratis. We stop at a total of three vineyards for tastings where the free wine keeps flowing.

The food on board is inclusive and ticks all the boxes. There’s lots. It arrives with joyous regularity and it’s all of an excellent standard. From a remarkably small kitchen the chefs trot out a la carte meals for lunch and dinner, generous spreads ranging from kangaroo to lamb and salmon as well as bespoke vegetarian meals for this fussy Kiwi. Munching fresh salad as the river drifts by.

The Murray holds a special place in the heart of South Australians. Two centuries ago, it was a busy highway into the hinterlands, north of Adelaide. Along the way are once-bustling river ports and kooky Outback towns, hours from the capital by dirt road, still to be “bitumised” as they say around here.

A mixed blessing. Rough roads keep the weekenders away.

Morgan is my small-town pick. The dusty red tracks on the outskirts have terrific names like Lovers Lane and Slaughterhouse Rd. There’s a perfectly preserved Victorian morgue.

But the piece de resistance is a curio shop that must have carried out its last stocktake during the Hawke administration.

Past the counter, holiest of the holies: the tapestry room. Gold coin donation. Covering all four walls, a floor to-ceiling collection of kitset tapestries made by the owner’s mother.

You know the ones: those sew-by-number editions. Eclectic scenes ranging from old masters paintings, to lions, unicorns and 80s soft-focus porn, including topless women with blow waves. The overall effect is staggering.

She sewed till she was 99. Her daughter wasn’t sure whether it was the tapestry or the bowling that held the secret to her mum’s longevity. In between marathon sessions with the needle and thread she took the Passat into Adelaide twice a week to bowl. Tenpin bowling. “Don’t believe me?” she says, showing me a photo of a bowling alley fundraiser.

Her late mum’s parked between the flashing white teeth of two Wheel of Fortune hosts.

Just by the by, the bric a brac is brilliant. I came away with some rare West German pottery. Collector, not a hoarder. Then, the horn sounds and we’re off again, never in one place for long, always the quiet imperative to get back to the boat so we can resume our meditative progress.

At night, we tie up to big trees along the water’s edge. Cockatoos, cormorants and herons for neighbours. Dave’s friends would question him on this aspect of the cruise. What do you do in the evenings, there’s no nightlife, you’re miles away from civilisation? “That’s why I keep coming back, no cities, no towns, no hoons,” says Dave.

For the stir-crazy, like yours truly, who can’t always feel the serenity, the answer is to get up with the dawn chorus, skip down the gangplank to the riverbank and run along the scratchy pathways. Exchanging notes with kangaroos over who got the biggest fright when they leapt out of the bushes.

Once, just once, I nearly missed the boat. Captain Terry knocked on our cabin door telling mum he was looking for her errant son. They sounded the big horns a couple of times, but I had my buds in, playing Nick Cave ballads. Upon return there was my mother on deck in her nightie and windcheater. “It’s all right,” she had assured the captain, “he always turns up”. Bad penny.

It has to be said the cabins aren’t exactly enormous. I hadn’t shared a sleeping space with my mum since a ski trip when I was 13. Never this compact. Two single beds side by side, a wardrobe, desk and set of drawers, shower toilet and basin. All in about 3sqm. You couldn’t have swung a catfish.

Mum told me this was positively capacious for ship travel. In her days sailing to Europe in the 1960s there was no en suite and they’d have squeezed in another two berths. I’m reminded of the Somalian saying: When you don’t want to be with family then a 10 bedroom house is not big enough. If you want to be together a small mat is plenty. And it was.

Dave points to some old red gums with huge scoops out of their sides. Rather than chopping them down the First Australians would harvest the bark, peeling it off in one piece to make a canoe. I imagine them sitting gingerly in their dugouts, dodging pelicans, taking a flame across the river to light cooking fires on the other side. More than just an abundant food source, in such a dry country the Murray holds a sacred place in the landscape.

At Ngaut Ngaut archaeological reserve we are guided to the base of a riverside cliff. The path to the top has been climbed for 8000 years. Forensic examination of the fire pits revealed that their ancestors had occupied this site continuously since 6000BC. It’s a tenancy that underlines the temporary nature of our whitefella footprints.

The cultural cringe of the over-privileged visiting the under-represented is diluted by savvy guides from the Nganguraku people. Telling us that when they decided to open up their ancient encampment to the public, the state government expressed bureaucratic concern about rocks falling on visitors’ heads. The locals told them the cliffs were made of clay. To their knowledge – eight millennia of it – no one had ever been injured by a rock. “But the government sent us hard hats anyway.” Our guide points to a pile of plastic headgear. “So we have to wear them.”

Distrust of the state and a nostalgia for yesteryear set up common ground between our age-experienced party and the Nganguraku guides. A relationship cemented by the proud respect for their older folk. “The men would come back to these fires with their food from the hunt, the women would cook it. No one ate until all the old people had woken.” Much nodding of passenger heads.

The guides told a familiar story about run-off from dairy farming. Sediment and nitrates flowing into the Murray undermining their food source. And there’s also a unique ecological travesty, a plague of introduced carp destroying native wildlife in the river.

Schlepping up 200 steps to the middens at the clifftop is too strenuous for half our group. Those who go, go slowly and carefully. Being certain of my feet feels like a luxury, part of me wants to sprint up the steps just because I can. I give myself a talking to. Remember the rule. Elders eat first.

Next day, I ask Dave how he’s doing this morning. “Well I woke up,” he says. He’d just lost his cat and put his wife who had dementia into a nursing home. This is the first cruise he’s been on without her. I get a greater understanding of what a triumph it is to greet every day with a smile when you reach that age. Dave’s therapy? He gets up with a stuffed toy and tells a shaggy dog story about how he’s keeping a moggy in his cabin. The dinner crowd love it.

Bill’s the actual on-board entertainer. Apparently he used to play with Acker Bilk. His world-weary face suggests an even more exciting past. Maybe he was a mercenary, we joke. He knew things, for sure. Like how to roll out the barrel and when to hold ’em, when to fold ’em.

As we queue to get off the boat, there’s a darling couple getting slowly out of their cabin.

I’d seen them about. Travelling companions who’d both lost their partners. More than 180 years between them. Although I’m itching to disembark, I remember my manners and urge them to go before me. He shakes his head. “No son, we’ve got all the patience in the world.”

And that, I thought is how you age well.

Sоurсе: nzherald.co.nz