Sponsored Listings:

Looking out at the vast tidal mudflats of Cooya Beach, most of us would see a barren wasteland. But Juan Walker knows better.

“See these little swirls?” he asks, pointing to the ground. “Well, it’s worm poo. They live under the mud and stingrays come and suck them up. At night if you shine a light you’ll see hundreds of stingrays.”

As a child, Walker and his brothers spent their days hunting for mud crabs and foraging for pipis and clams along these shores near the mouth of the Mossman River, just north of Port Douglas, learning the traditions of the Kuku Yalanji people from their grandparents. As an adult, he still spends his time pretty much the same way, But now he’s the teacher, passing on his knowledge to tourists keen to know more about indigenous culture.

Walker’s older brothers, Linc and Brandon, began leading cultural tours in 2006. He worked with them before starting his small group tours two years later, joking that as the youngest brother he got given all the bad jobs.

Walker explains his unusual name came about because his great-grandmother was from the Torres Strait Islands and had three husbands. The first two were “black-birded” and taken to work as dive slaves. The third was a Filipino man who was fishing in the islands, hence Juan, his Spanish name.

Our tour begins with a quick lesson in spear throwing on the beach. Walker shows us how to hold the weapons, and instructs us to aim, step forward and flick. “Point a finger at the back, palm up, and let him rip,” he says. My first two attempts flop a few metres away. Walker swaps me to a smaller, lighter spear. It arches high in the air and lands pointy end in the ground, and I feel a tiny bit proud. Then he throws his, and it lands about 30m away. But that’s nothing. He says the farthest he has ever thrown is 35m, while the world record is 124m.

We walk barefoot across the mud towards a lone grey mango tree that juts out of the distant horizon. “Think of this as a free pedicure,” Walker says. He explains that indigenous Australians look for different food sources depending on the season. At the time of our tour the weather is cool, which is ideal for shellfish. Around a full moon, the current is also stronger, so the crabs eat more and fatten up faster.

We change direction and continue wading through the warm shallows towards the mangroves. Walker catches a mud crab for our lunch but all I manage is a leaf. “That’s for vegetarians,” he jokes. Searching the mangrove roots, we find sea snails, periwinkles and oysters but Walker warns these must be cooked to eat because they suck bacteria from the trees. “These mangroves are really special. You’ll never run out of food here.”

Across the road at Walker’s mum’s house, we wash our feet under the garden tap before going upstairs to the kitchen, where he cooks our bounty with freshly picked chillies. Then we sit on the veranda and savour the succulent flesh, sucking the juice from the shell.

“Make a mess,” he says. “If you’re not making a mess you’re not doing it properly.”

As we eat, Walker shows our group three boomerangs of different shapes. To our surprise, he says there are more than 30 types of boomerangs found in Queensland alone, and only two or three styles are carved flat on one side and curved on the other so they return. Some are suitable for catching small animals such as bandicoots, goannas and possums; others are specifically made to snare wallabies. He then plays us tunes on a didgeridoo that sound like dingoes howling and kookaburras laughing and shows us how to check if it is authentic (“not made in Taiwan”) by feeling inside for termite tracks.

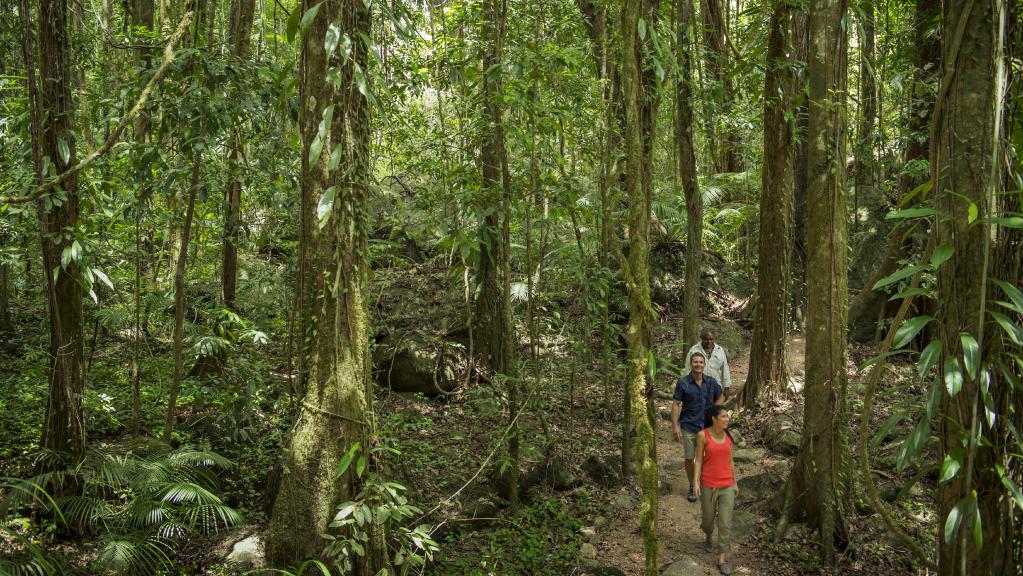

Just down the road at the southern end of Daintree National Park, the oldest surviving tropical rainforest in the world at 100 to 150 million years old, lies Mossman Gorge, where we take a Ngadiku Dreamtime Walk with indigenous guide Aaron Minniecon.

After a traditional welcome-to-country smoking ceremony, we follow the old hunting and gathering trail. Minniecon points out mossy red cedars used to carve dugout canoes and clubs and shields used in warfare. As we pass sacred areas, he calls to his ancestors to let them know we are friends. He shows us grinding stones beside the path that his ancestors used to crack nuts, and ochre, a natural earth pigment that comes in 18 colours ranging from yellow to brown and used as face paint for special occasions.

Art is integral to indigenous culture, and tropical north Queensland is dotted with cultural centres and galleries where artists come together to work and showcase their offerings. Many also display their work at the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, held each July.

At Canopy Art Centre in Cairns we meet Glen Mackie, who retells the myths and legends of Yam Island in the Torres Strait, where he was born and raised, through vinyl cut prints. He says the island is known for warfare, dugong and turtle hunting and collecting shells.

“My grandfather taught me the carving design,” Mackie says. “He used to draw the designs in the sand when I was in primary school, and in high school he showed me how to carve on wood. Every design means something. This means crocodile, this is shark,” he continues, pointing to his works. “I use [those] designs because they’re my parents’ totems. I also make my own designs.”

Mackie moved to the mainland 15 years ago. “My Dad has a crayfish factory and store, but it wasn’t for me,” he says. “I’m the only artist from Yam Island and I saw it as my duty to educate people and tell them the story of where I’m from.”

His works are now exhibited at the National Gallery of Australia, National Museum of Australia and Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane and his murals sell for up to $16,000, but he says he doesn’t care about the money.

“I’d rather educate people about my culture.”

DRESSED FOR THE DANCE

Dust swirls as dancers, glistening with sweat, stomp their feet on the dry, brown earth to the banging of clapsticks and drone of the didgeridoo.

Children in traditional costumes, their faces painted with ochre, stand on the side, eyes wide and mouths agape, watching as they await their turn. Elderly ladies, their faces swirled with white, sit on plastic chairs in a row clapping, whistling and laughing raucously as their families perform.

Over three days, dancers young and old from 20 Cape York communities take to the stage to enact their stories at the Laura Aboriginal Dance Festival.

Some wear elaborate headdresses, others simple loincloths, their skin painted with hand-prints. Some perform traditional hunting dances, prancing with spears poised in time to the beat. Others hold their arms out to the side and soar like eagles across the festival ground.

An elder in a bright orange T-shirt emblazoned with the word Hawaii is so moved by the performance she kicks off her shoes and joins in, promptly stealing the show.

Children in the audience mimic the dancers, and it fills me with hope to see indigenous culture being so enthusiastically preserved and passed on to the next generation.

CHECKLIST

Walkabout Cultural Adventures offers small-group, half-day tours for $165 a person or full-day tours for $209 a person, with pick-up from Port Douglas, Mossman and Daintree Village.

Ngadiku Dreamtime Walks at Mossman Gorge depart daily; $68 for adults and $35 for children 5-15 years; mossmangorge.com.au.

Sоurсе: theaustralian.com.au